Ringdocus, Start of a Journey

Part 1 of a preview and behind the scenes of The Ringdocus Project*

*The full book can be found on Amazon

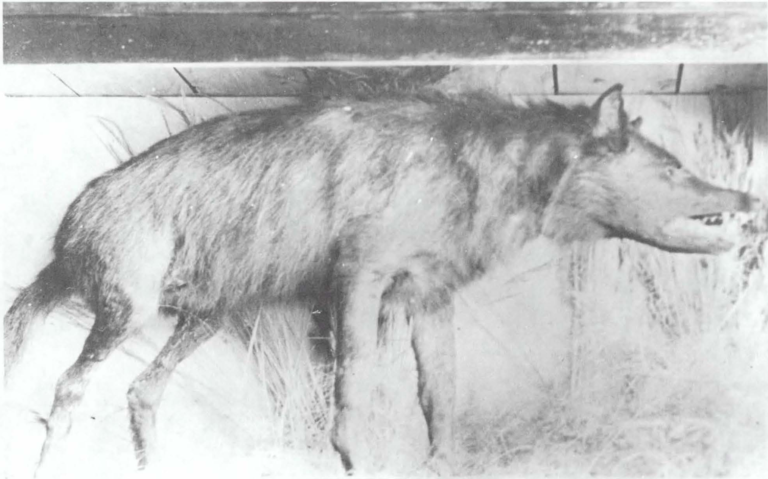

If you were to ask a cryptid enthusiast about the Shunka Warak’in, chances are they’d respond with a question of their own: what is that? This obscure cryptid began as a black-and-white photo of a missing taxidermy mount found in a few cryptozoology books. The subject of this photo is a strange-looking canine resembling something of a cross between a wolf and a hyena that Montana rancher Israel Hutchins shot in the winter of 1886 – ’87, the hardest winter the Madison Valley had ever seen, preceded by a dry and fiery summer. These conditions brought the odd-looking predator directly into the path of the ranchers in the valley, including Hutchins.

After shooting the animal dead, Hutchins took the carcass to taxidermist Joseph Sherwood in exchange for a cow. Sherwood kept the animal on display in his store/museum in Henry’s Lake, Idaho, until around 1987, when the mount went missing, leaving only the photograph, Hutchins’ tale, and theories about its identity to be recorded in a few select books. Due to limited evidence and nearly nonexistent recorded sightings outside the Hutchins account, the information accompanying the photo is always the same, and the theories, confusing.

Point number one of the confusion: the name Shunka Warak’in, under which this photo is classified, comes from a legend told by the Ioway people of the Midwest. According to book entries, the Shunka Warak’in is a cryptid of the Northwest, specifically Montana and Idaho. How does a Midwestern Indigenous legend explain a Montana monster?

Point number two: the leading theory, outside of a botched taxidermy job, for what this animal could be is a surviving Borophagus, a primitive canine that bears little resemblance to the creature Hutchins shot.

It was these points of uncontested information that drew my attention to this cryptid in particular and started my journey of giving this intriguing animal more attention and an accurate story that no one else seemed willing to give it. It wasn’t an easy journey to start. These theories and the available information seemed to come out of nowhere, with no trail to follow.

There had to be more to the story, but where to find it?

It was in a book that had nothing to do with cryptozoology where I found the start of that overgrown path of research. The book was Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives & Evolutionary History. This book contained anatomically accurate sketches of the canine family’s primitive members. When my eyes landed on a reconstruction of a Chasmaporthetes head, there was instant recognition. This ancient North American Hyena had a nearly identical head shape to the Shunka Warak’in, or Ringdocus, as the mount was also called. Thus, started my mission to really understand the cryptid and uncover that the connection to the Ioway legend came from a researcher of that nation in the modern day, and that the Borophagus was likely a scapegoat only because they were the most prominent family of prehistoric dogs and had the nickname “hyaenoid dogs,” which had nothing to do with their physical appearance.

Those two points were only the start of my research, and I uncovered a lot more the more I dug. If the right questions are asked with the goal of finding genuine truth, even the coldest cryptozoology cases can reveal new information. The key is to make your own inquiries, even if a piece of information seems factual, and to maintain an open mind. The beauty of cryptozoology is its uncertainty: it leaves the door wide open to new discoveries and ways of understanding the world.