Stories of werewolves came to the area with immigrants from Romania and Russia. Children born on Christmas were cursed to live out their lives with lycanthropy, or that of the werewolf. Some believed it was a punishment for being born on the same day as Christ and disrupting the Savior’s birthday. Some believed it was due to the liminal timing of their birth. The 12 days between Christmases were thought of as days outside of time, so the children were born unfinished, and as liminal creatures due to the thinning of the veil. Adult werewolves were thought to be most active during the twelve nights, as well.

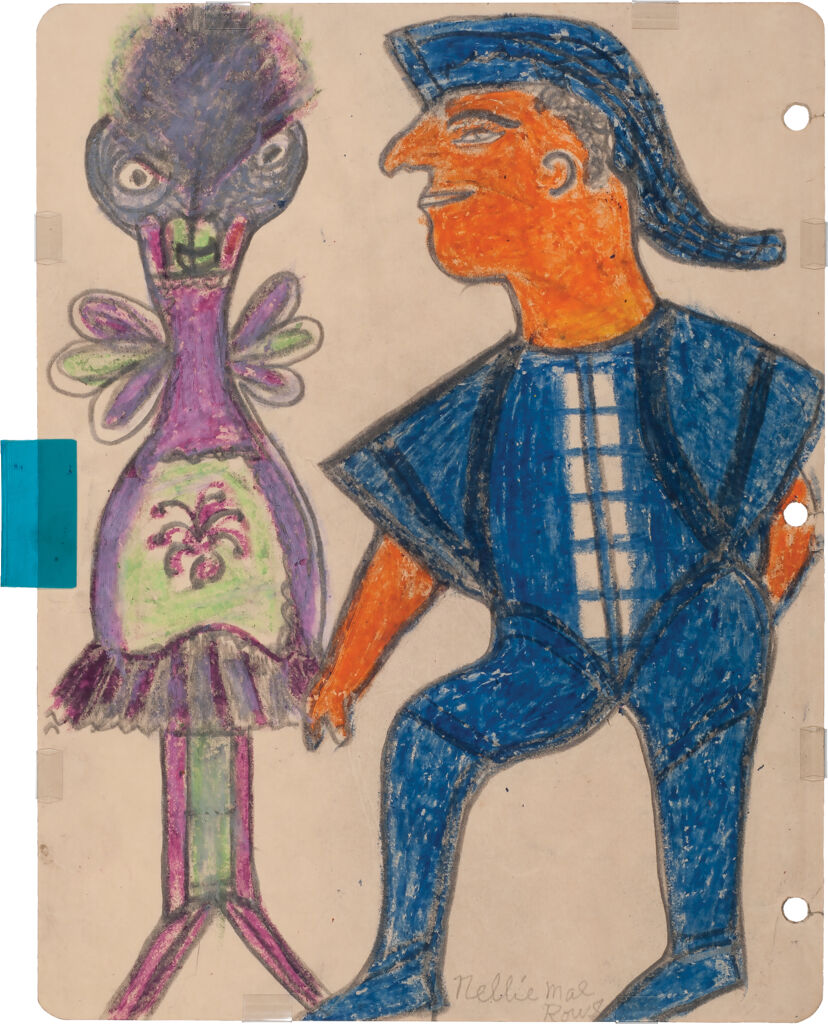

Appalachians believed just to speak of the wolves would manifest them, and the wolves would tear off their limbs. So, during the twelve nights, they referred to werewolves, winter witch-wolves, and hexxenwolves as “pests” or “enemies”. They stayed mostly indoors due to the belief that the cold encouraged the spirits in them to shapeshift. Alpine immigrants brought stories to the mountains of wecklin witches like Perchta and Holda, who led armies of unbaptized children’s souls, or souls of those who died violent deaths before their time floating through the streets and above the clouds.

Just as with the wolves, the stories of witches brought warnings of harm and punishment. Cautionary tales to keep us close to the heat of the hearth and out of danger when winter showed its teeth.

Even trick or treat traces its sickly-sweet origins to the snowy season. Pennsylvania Dutch residents in West Virginia celebrated the season with Belsnickeling, or choosing an elder to dress in ragged robes (Belsnickel literally means Nicholas in fur), going door to door asking families if they’d been naughty or nice and dolling out rewards or punishments accordingly. When similar Scotts/Irish traditions of Samhain entered the region, eventually the two customs melted together, and memories of Belsnickel faded away with the rise of modern Halloween and trick or treat.

Parades and festivals meant to mark the end of the harvest season and open the winter were originally celebrated on St Martin’s Day on 11/11. But as agricultural advancements began that allowed fodder to be grown later into the season, the end of harvest was extended first to St. Andrew’s Day on 11/30, then to St Nicholas’ Day on 12/6, then finally landing smack in the middle of the yuletide celebrations on St. Thomas’ Day on 12/21. Children would celebrate by donning masks and going door to door while holding candles inside hollowed out pumpkins and turnips.

As the Victorian era took hold, Christmas became a sweeter and more sanitized version of itself. The gruesome ghosts and ghastly ghouls were left out of the narrative, slowly sliding over time into the traditions of Halloween. Some folks have forgotten the Night Hags, the Goat Monsters, the Soul Birds, the Night Folk, and all the other legends of the time and the roles they played in our holiday celebrations. They’ve forgotten the rules and superstitions that kept our ancestors safe during the darkest nights. But the dark holds memories and the mountains remember.

So, this Christmas when the fire dies down leaving only embers behind, listen close. When the wind makes its way through the valleys, can you still hear them? Can you hear the haints, the maskers, and the shapeshifters walking the hills? They are the ones who haunted our region long before the plastic pumpkins and porch lights of Halloween.

If you pause between the clatter of carols, you might sense those spirits stirring, just waiting to be remembered.